3 Keys to Writing Effective Action Scenes

Today’s guest post is by Remy Wilkins.

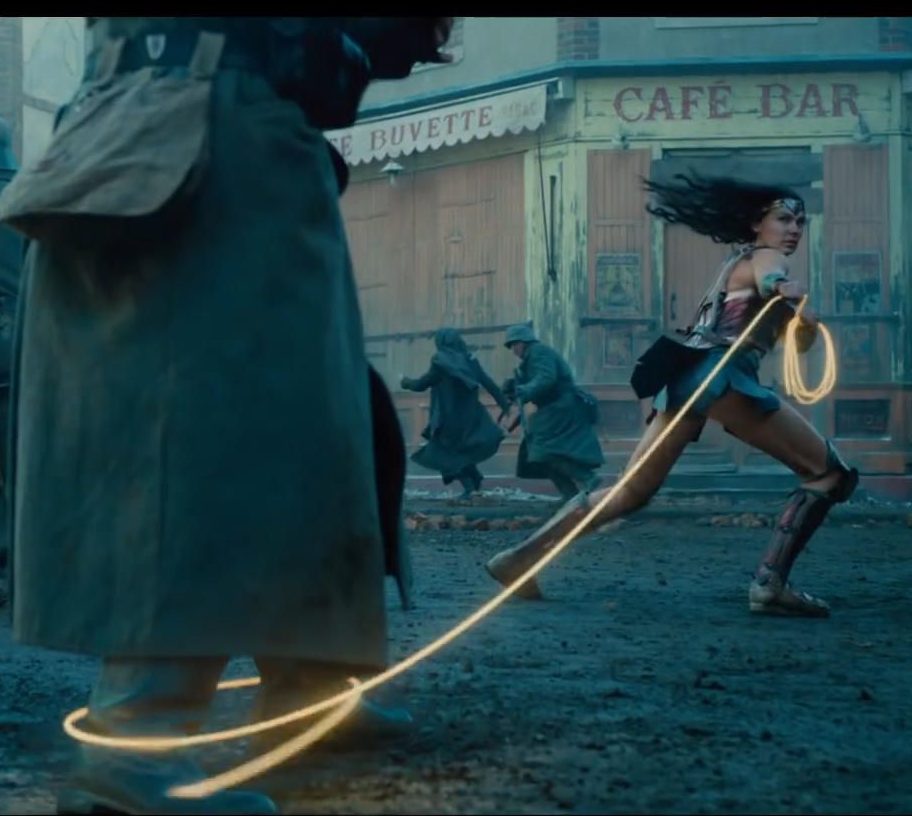

We all want our climaxes and battles, our chase scenes and explosions, to be as dynamic and blood pumping as the summer’s best blockbusters, but the difficulty is that the strengths of cinema—its visceral visuals—do not easily align with what’s exciting in a novel.

But this doesn’t mean our action sequences are relegated to flat descriptions that must wait for a movie adaptation before becoming exciting. There are plenty of evocative scenes that drag the reader through finger-biting excitement and fear, but it’s a tricky balance of details and space enough for the reader to flesh it out.

Many writers err on one side or the other; they either overload the scene with too many descriptions or speak so sparsely about the events that the reader misses the drama.

In considering these pitfalls, I sought inspiration from movies on how to write compelling action scenes, looking for tips that I could apply to prose. As I studied both good and bad action sequences I found three keys that separated the effective scenes from those that were ineffective.

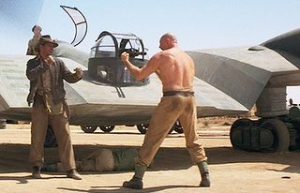

As an example I’ll refer to the airplane scene from Steven Spielberg’s “Raiders of the Lost Ark” (a clip which can be found on HERE on YouTube.

The First Key: Using Your Setting

It seems obvious that you need to tell your reader where the action is occurring, but it has to be more than a token mention, and the details used need to be incorporated into the scene.

What is the purpose of mentioning the rusty barrels in the corner of the warehouse if they aren’t incorporated into the action? A failure to use the setting is like fighting blindfolded. You’re flailing around in darkness. It’s like a green-screen action sequence where the stakes are as fake as their digital setting.

A good action sequence is going to set the stage with all the elements necessary to give the reader a full understanding of the space, while also foreshadowing both new threats and twists.

Consider the airplane fight from “Raiders of the Lost Ark.” First, Spielberg gives us a nice wide shot, showing us all the set pieces and how they relate (the plane, the fuel truck, the pilot, the mechanic, and the shed from which the big man emerges). Then the camera settles in behind the oil drums, where Indy and Marion are hiding.

The whole space is even delineated with a white circle, defining the place of action. The viewer knows where the action is taking place and can see the threats. They may not recognize the danger, but we have two bad guys, some explosives along the margins, and a shed that may hide more danger. The setting is used: dirt is thrown, gasoline is set to flame, propellers aren’t just props.

What this means for a writer is the space needs to be laid out so that the reader feels it.

The reader should know where the characters are as they move around. If your characters are fighting in a kitchen they need to bump into cabinets and break dishes. If they’re in the forest, they need to duck behind trees and trip over their exposed roots.

If your setting isn’t an active participant in the scene, then you need to ask yourself why the scene is set there.

The Second Key: Showing Danger and Seeing Danger

This is something everyone does, but not everyone does it correctly. Every writer mentions the danger and then shows their characters seeing it, but the difference between a good action sequence and a bad one is the space between those two things.

If you ever find yourself springing danger on your characters and following it up with your character’s response to it, then you haven’t  given sufficient space for tension to grow.

given sufficient space for tension to grow.

I’ve seen it done poorly in a couple of ways. The writer will have their characters introduce the danger with a cry (“Look out—the wall is falling!”) and then describe the danger as it happens. Or the danger is described followed by the reactions of the characters.

Note how carefully Spielberg sets up the danger (the wrench in the propeller, the oil cans) and note how he makes sure he shows his characters see the danger.

It isn’t enough to show the gasoline and the fire, we have to see Marion seeing the gasoline on fire. We have to see Indiana put it together and recognize the oncoming explosion. All the threats in this scene are set up by earlier shots.

The reason for this is that danger needs breathing room to be effective. Danger needs to be foreshadowed (“The bridged groaned under their weight”) and even noted by the characters (“I don’t think we should cross this bridge”).

Giving danger the space to expand its effect is what will ultimately cause the reader to speed up in anticipation. A surprise (“Suddenly the killer appeared behind them”) will cause the reader to slow down, looking for possible clues that they missed. Tension arises from anticipation, and for anticipation to grow, there has to be space between showing the danger and seeing the danger.

The Third Key: Escalation

The third and final key to an effective action scene is escalating the danger during the scene.

Again, instinctively many writers already do this, but being intentional about it will only help you. This should be true of the entire narrative, of course.

Consider Pixar’s Wall-E, which begins with our lonely protagonist wanting to find love. The stakes are relatively low, he has a friend, he enjoys his job, and he has all that he needs to survive.

But once he meets Eve, his life becomes increasingly dangerous. His goal shifts from finding his Eve to chasing after her, assisting her in her mission, fighting the evil robot, fighting for his life, and saving humanity. The stakes start low and escalate until the stakes are high, his life and the future of life on earth hanging in the balance.

This escalation applies to individual scenes, as Spielberg demonstrates. Indiana first hopes to sneak up on the pilot to take the airplane, but he’s caught by the mechanic and must resort to fisticuffs. He deals with the mechanic (foreshadowing the danger of the propellers), and then the big guy shows up.

Indy quickly realizes he can’t win that fight and begins to run. Spielberg isn’t finished cranking up the danger, however, as the pilot pulls out a gun. So now Indy has to avoid a gun and a big guy. Even though some tension is released (Marion knocking out the pilot), overall the danger is increased (Marion getting trapped, the plane starts moving, more soldiers, Indy has to avoid getting crushed by the wheels and then loses his gun . . . you get the idea).

Indy quickly realizes he can’t win that fight and begins to run. Spielberg isn’t finished cranking up the danger, however, as the pilot pulls out a gun. So now Indy has to avoid a gun and a big guy. Even though some tension is released (Marion knocking out the pilot), overall the danger is increased (Marion getting trapped, the plane starts moving, more soldiers, Indy has to avoid getting crushed by the wheels and then loses his gun . . . you get the idea).

Just as your novel progresses from bad to worse, so too, each scene needs to follow that same pattern. If the house catches fire, the stairs need to collapse, and someone needs to twist an ankle. If the horses break loose, the sun needs to go down, and a wolf needs to howl. Danger needs to steadily constrict until your character’s hope is a thin filament he desperately clings to.

Make sure your setting is working with you and not some useless backdrop. Pore over your action sequences looking for ways to add that space for tension to grow. Add a rumble of footsteps before the evil reinforcements appear, show the rope begin to fray, give the reader a chance to put together the next tragedy to befall your characters.

And always be turning the screws. Remember, stories are not made by events, but by tension.

Remy Wilkins is a teacher and author. His first book Strays, an adventure story, is out now available from Canon Press and Amazon His second novel will be out next year. You can follow Remy on Twitter.

Remy Wilkins is a teacher and author. His first book Strays, an adventure story, is out now available from Canon Press and Amazon His second novel will be out next year. You can follow Remy on Twitter.

Thank you for giving clear examples from movies in this post. I wish you could have had some written descriptions (copyright issues?). How does one describe a punch and its aftermath using words? Should the writer get into a painful hand from punching, or does that come later? How does a writer describe being hit and losing consciousness? I’ve seen many action scenes in films but would appreciate a resource for a writing fight scene.

Genre: Fantasy

I belong to the Woodlands Writing Guild in The Woodlands, TX. A couple of us Guildies who write fantasy are followers of yours, just FYI. I am a year into the planning of my first fantasy novel. I am using your 12 pillars approach with a smattering of Brooks and Weiland thrown in for odds and ends info. I have a question: Using your 10-20-30 technique, can sub-plots be a story that involves the antagonist [RE: Jean Auel-The Valley of Horses, ’82 – there are two different stories lines which merge about halfway through the book, although this is not Protagonist vs Antagonist, I refer to the alternating of story lines]; does this work with your 10-20-30?

Hi John, more than one timeline can be structured the way a subplot is structured, in terms of scene placement. And, with your example, you can have a subplot with an antagonist or any other character and have the two meet at some point (usually it’s at the climax, if at all). Lots of ways this can be applied. Some of those “old” novels don’t have the best structure (or at least what’s expected by readers these days). I was a huge fan of Jean Auel’s books, but they did have a lot of narrative and telling.

Yes, Jean did have a lot of telling and narrative but I’m sure it was because she never met or had the benefit of your excellent guidance.I do like the way she brought two storylines together, with 2 protagonist merging, to build a strong story series premise

. From that point forward, I guess we have protagonist 1 and protagonist 2?

Happy trails, John

Hi Remy, Thanks for sharing this awesome article!

To write effective combat scenes in thrillers, you need to be concise, considerate of emotion, and realistic.

Please read my blog: The Do’s and Don’ts of Writing Combat Scenes in Thrillers

Hope this will also help, thank you!