How Writers Can Create Continuity in Showing the Passing of Time

Continuity is so important in a novel. Readers should be able to move from one scene to the next without effort. Without struggling to figure out when the scene is taking place and how much time has passed since the prior scene with your characters.

Scenes are strung together, like pearls in a strand. Each should be flawless and beautiful and contribute to the overall effect of the story. One of the ways to ensure your scenes are strung together effectively is to examine the way you move from one scene to the next.

We’ve covered most of the items in my scene structure checklist since the year began, and I hope these posts are helping you to get scene structure under your belt. Faulty scenes are the most problematic issue I see in the critiques I do, and that’s why we’re taking time to go deep.

In this post we’re going to look at this item on the scene structure checklist:

___ My scene clearly indicates how much time has passed since the last scene with these characters as well as the previous scene in my novel (if different)

Clear Passing of Time

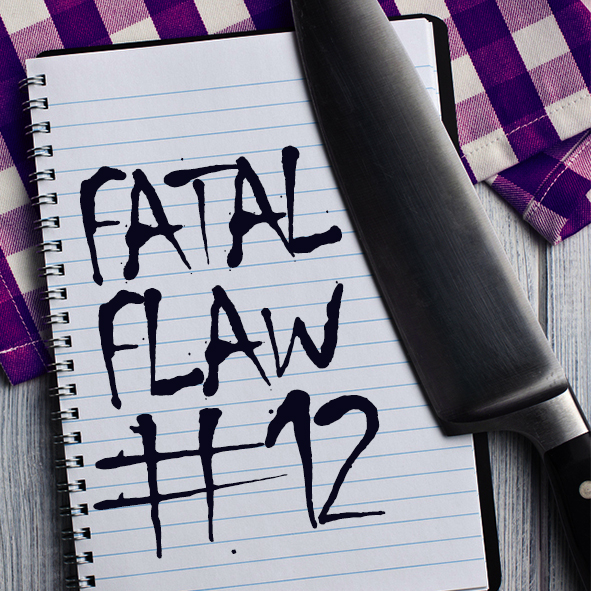

I don’t want to struggle when I read a novel. I want to turn pages effortlessly and not trip up. Some things that trip up readers are wordiness, vagueness, weak sentence construction—all those flaws we looked at last year and that are explored in great detail in 5 Editors Tackle the 12 Fatal Flaws of Fiction Writing.

Now that the book is out, you don’t have to worry or wonder what flaws your writing reveals. My hope is that by studying those twelve flaws and learning to identify and catch the sneaky culprits, you’ll eliminate them from your writing.

But there are some other things that trip up readers, that break the continuity of the reading. Failure to have smooth transitions from scene to scene is one surefire way to do this.

Some scenes begin right in the same moment, and with the same characters, as the prior scene. Those scenes are never problematic. It’s clear when the new scene is taking place. If the writer is still in the same character’s POV as before, the shift from one scene to the next presents little-to-no problem.

If you are using this structure with some of your scenes (and you probably are), be sure, if you switch POVs, that you indicate right away that POV change. If this next scene is continuing in time but changing characters and setting, you need to keep some other points in mind:

- Be careful you don’t slip into omniscient POV or author intrusion when you start the next scene. Phrases like “In the meantime . . . “ or “Meanwhile . . .” jump out of POV.

So do bits like “Three miles away [or “ten minutes later], John drove to his cabin.” In John’s POV, he doesn’t know he’s three miles away from what just transpired, and he isn’t thinking about that. This is a common mistake that writers often don’t realize they’re doing.

- Readers will assume what happens next/now in this new scene is picking up right after the previous scene, in time. You don’t need to put a “time stamp” at the top of the scene to state what time it is (more on that below).

And a side note: because this is presumed, you don’t want to have this new scene starting earlier in time. Keep your scenes in time order. If needed, grab a partial scene and move it to the right place in your story so time is always moving forward (unless you are clearly doing a flashback, and that would need to be clearly conveyed).

Get my cool FREE ebook: Manipulating the Clock—How Fiction Writers Can Tweak the Perception of Time. A special gift for subscribing to my newsletter–not available for sale anywhere online. Click here to get your free ebook!

If you are using shifting POVs in your story, it’s especially important that you make clear the passing of time. If your new scene is not a continuation from the prior scene, you don’t need much to indicate when your scene is taking place. If you are sticking with the same POV character, a phrase like “later that afternoon” or “the next day . . .” works just fine.

You can also indicate time passage in the opening paragraph or two by having the character think or talk about something that makes clear how much time has passed. If the prior scene showed Diane at work, arguing with her boss, the beginning of the next scene could have a line like: “Diane ambled into her apartment and threw off her shoes, glad her workday was over.” You don’t need to say “Three hours later” or put the time at the top of the scene.

Time/Date Stamps

A word about time/date/location lines. I personally don’t like them. Those are the lines at the top of a scenes that say something like “Tuesday, 3 p.m., Roger’s apartment.” First of all, all this information can be brought out in the scene itself. Second, readers often gloss over these. Third, how important is this? Probably not very. Fourth, it’s telling, not showing. Show Roger in his apartment and that it’s the afternoon.

My fifth complaint is the most egregious. Writers often expect their readers to do the math. This is really annoying when scenes jump around in time. You’ll have dates, but nowhere is it shown or indicated in the scene that it’s taking place six months earlier or two weeks later. Instead, you are given “May 6, 1967.” The last scene had a time stamp of “July 15, 1999.”

In order to make sense of the action and follow the story, the reader is required to stop, flip back to the last scene, note the time stamp, do the math, and calculate just how much time difference there is between scenes (and, worse, what direction in time the shift is headed).

Seriously, readers are not going to do this. These writers expect readers to not only pay attention to those time stamps but to do a quick calculation in their head at the start of every scene to prepare to read further. To me, this is worse than having algebra homework.

It’s helpful in a prologue or first scene to establish the date, if it’s not present day. That’s all you’d need. The place and time is better brought out in the scene itself (if you even need the exact time—usually you don’t). Some genres like thrillers use these time/date stamps religiously. They are meant to add suspense, when the clock is ticking. However, I still don’t pay attention to lines like “Tuesday, March 3, 3:57 a.m.). Maybe it’s just me, but I don’t stop to think about the day and time.

So with a historical, I’ll write at the top of the opening scene only: July7, 1876. I don’t give the place or the day of the week. Or the exact time. The place will be revealed in the scene, as will the general time of day.

With Colorado Hope, the prologue takes place six months before the actual story begins. So with chapter 1 I include “Six months later” at the top. I don’t make the reader do the math.

You can put the date in or not, but what’s important is to get that passage of time clear. My character is not going to be thinking “Huh, it’s now six months after I lost my husband in the flood.” So using that simple time stamp helps the reader quickly know where the story is picking up.

A few chapters later, the story picks up again in a new act about eight months after the previous section. Again, at the top of the new section’s scene I put “Eight months later.” Those are the only times I’ll put in a time stamp. If your story is continuous and you don’t jump ahead to another time period to continue, you don’t need to indicate the time passage like that.

And if you’re doing a flashback (if you must), don’t use time stamps. Same issues apply. Just show where and when your character is, in a tasteful, artistic way. I’m not a fan of long flashbacks that take up pages (or are separate scenes). There are certainly good uses for flashbacks, but beginning writers often use them when they’re not needed and don’t add anything important to the story (and this is the topic for another blog post).

While we’re not talking about overall novel structure in this post, this is a good place to mention that novels shouldn’t cover huge amounts of time—not unless you’re doing an epic family saga covering generations or a fictional biography of someone’s life. Novels should have a tight scope, just as scenes should. They are also capsules of time, rarely covering more than a few months.

If you keep in mind that novels are about a protagonist going after a short-term goal (for the most part), your scenes won’t be jumping ahead weeks and months and years. Novels that cover too much time lose focus, and they usually indicate a story that is not well structured.

When Shifting POVs, Give Readers a Reminder

While it’s assumed your story is moving forward in time, if you are moving around with characters, you might need to remind readers where you last left off with them.

I don’t mean you’d write something like “When we last saw Ralph, he was dangling from that branch over the raging Pecos River . . .” You’d just start right into your scene and put in enough information through the POV character’s thoughts, speech, and narrative to make clear he’s in the same place you last left him.

Or, if you now have him in a new place, find subtle ways to indicate how much later this scene is taking place than his last scene, and remind the reader where she last saw him. It’s not hard to do, and it should be done in the first paragraph if possible.

All this helps provide smooth continuity in the reading. The last thing you want is to make it hard for your readers to get through your book. You work so hard to write a terrific story and dynamic scenes, so don’t trip up readers by failing to make clear the passage of time.

What are your thoughts about time/date stamps? Do you sometimes come across novels that aren’t clear about time passing? What techniques do you like to use to show how much time has passed from scene to scene?

Want to nail scene structure?

Be sure to download my scene checklist and my scene template.

At whatever stage you are in with your novel, you can benefit by an outline critique. I charge this service by the hour, and you can be sure you’ll get a thorough analysis and critique of your story. Submit an outline for just a few chapters or your entire story. Your story will greatly benefit from this, and I bet you’ll not only be surprised at what you’ll learn through this outlining process, you’ll become a better scene writer.

Are you willing to take the challenge? Contact me to set up a date for your scene outline review.

Feature Photo Credit: Esther Cantero via Compfight cc

Never say ‘never?’ Perhaps rules are made to be broken. Scott Turow’s recent novel “Innocent” has time-jumps such that he frequently uses date/time stamps. My story has at least 11 time jumps (no flashbacks) where I think the stamps are absolutely required. Maybe one of things that makes Faulker’s “Sound and the Fury” so maddening is the absence of time stamps. (I believe he originally wanted to use different colored ink to show time changes, but no publishing house would agree to that). So, I will file this blog post as a rule to be honored in the breach!!

Hey, lots of books jump all over the place (yours do too!). In that case it’s essential. What I tried to convey is the writer should use them if they’re needed. With The Time Traveler’s Wife, it would have been awful if those time stamps weren’t used (and the notation of the characters’ ages at that moment too). So I would never say never! However, a lot of beginning authors use them with every scene and chapter when they really aren’t needed at all.

Gotcha. Point well-taken. Thanks, as always!

Perfect timing of this post. Am doing historicals and have “time jumps” (my story is based on true events). Glad to hear that Time/Date Stamps are OK at Act/Part breaks. But I currently have a couple of intra-Act/Part jumps where I’m considering using Time/Date Stamps or maybe just working the info into the scene openings. Or, maybe I need to rework the story! Thanks for this post.

It’s often a matter of style and genre. Some types of thrillers use them every scene. Which is fine. The key is, you don’t want to make your reader work hard to figure out your timeline. If a writer has to rely on time stamps to “tell” instead of showing in the scene how time is passing, it can be a weak crutch to cover bad writing. Glad this resonates with you!

Great information! Thanks for the pointers.

As always, another great post that makes me take stock of my writing! I had just been contemplating the fact that my 20k word novella covered the span of almost six months (two siblings going through military training, a number of leaps forward in time to cover a month of training without going into detail of a month of training). Working on making the story cover a shorter time frame with less frequent leaps forward.

Thank you for the insights.

Impressive and informative post. Consider me a new subscriber.

My editor (The Queen) and I have been paying strict attention to the passage of time in my forthcoming novel. The first eight chapters covers the events of a single day. Yes, we took special pains that it truly feels like the passage of an eventful day.