Fiction’s Magic Ingredient: The Scene

Today I’m breaking my tradition and hosting a guest blogger as we explore the topic of scene structure. Jordan Rosenfeld—novelist, writing instructor and editor—teaches extensively on scene structure, and I’ve been using her definition of a scene in these posts on this fifth pillar of novel construction: Plot and Subplots in a String of Scenes. She’s the author of Make a Scene, the best book available on scene structure, which I highly recommend all novelists buy and study carefully.

Scenes—those little capsules of action, information, and setting, are more than just a dull little way to practice “show don’t tell” in your writing. There’s a reason I refer to them as “fiction’s magic ingredient” when I teach: without scenes all you have is a lot of throat-clearing narrative, characters ruminating, and fancy words that gaze back adoringly at themselves like Narcissus of the Greek myths.

Even the prettiest sentences won’t make a story without the solid structure of one good scene after another. So here’s my shorthand for what scene writing really does: you create a stylized, “sexier” simulacrum of real life that readers experience as unfolding in “real time.” So let me break down what I just said here:

- Stylized.

Penning reality exactly as you find it is called reporting—leave that to newspapers. Fiction is a stylized reality. And, contrary to the idea of truth telling, so is memoir. You choose events, situations, people, and language toward a crafted outcome—keeping a story and character arc in mind, tension alive on the page, and your themes clear in your imagery and language.

By the time you reach final draft stage, the outcome you had in mind must be evident to your readers (first drafts are the place to discover, uncover, and explore what that outcome is. Later drafts are where you pare, perfect, and polish). Your goal is to shape a set of ingredients to have a certain kind of effect, to deliver an experience, not a dull, mundane reality.

In delivering an experience, you also want to consider your word choices (avoid clichés and hyperbole), your characters (or narrator), and the world(s) they inhabit—you want your writing to shine with its own unique spirit, to be unlike anyone else’s. And it’s through scenes that you do this.

- Sexier

Fiction should be “sexier” than reality. In fiction you leave the majority of tooth brushing, flatulence, bill paying, and the micro-minutia (turning door knobs, walking across rooms, and getting in and out of chairs) by the wayside. This is not to say that real life doesn’t factor in for your characters—it does. And for the memoir writer even more so, but only in appropriate glimpses. The rest of your scenes should be reserved for relevant or “significant” actions.

These actions can be character-significant, that is to say, they deepen our understanding of a character. Or they can be plot-significant; they drive your plot forward. Even for the memoir writers among us, who traffic in reality, the reality you choose to share on the page must be the “best of” or “greatest hits” version of reality—reality sharpened and honed to a high polish to drive toward a powerful understanding.

- Simulacrum

Your task, then, when writing scenes, is to give your readers a “simulacrum” of real life—meaning “a likeness” that is sharper and more dramatic than the real thing. You want to create for your reader the sense that they are caught up in the center of action, tension, and emotional intensity (not to be confused with melodrama).

- Write in real time

Or, as you’ve probably heard enough times to gag at the sound of this phrase: “Show, don’t’ tell.” Or, as I prefer to think of it: “Demonstrate, don’t lecture.” Readers participate emotionally with the written word when there are several main ingredients at work:

- Compelling, though “complex” memorable character(s).

- Detailed (though not over-the-top) visual setting (don’t get bogged down in describing your setting).

- Action: Movement, gestures, dialogue. Action happens when characters interact with the setting and each other. Refrain from passive action in which your protagonist is merely watching. Action also creates the “real time” portion. When there is movement, we experience a sense of “time passing.”

- Emotional dramas. Conflict. Consequences. Suspense. Tension. The potential for trouble or danger. This is how we come to care about the people in your story.

- Plot. A matrix of events, beginning with a significant situation that leads to further consequences. “Something new” is revealed to the reader in each scene, until some sort of climax and resolution results in character transformation. Plot is the “why”—the reason for your story’s existence. Without this engine driving us forward, all we have are lovely little vignettes but no sense of a guided experience, crafted for a reader’s pleasure and understanding.

Scenes Require a Beginning, Middle, and End

Just like a story itself, scenes themselves have a loose “beginning, middle, and end” construction. Many of us write scenes intuitively and often don’t quite know if we’re done, or if we “did enough” in the course of a scene. Therefore, you should have an intention or purpose for each scene.

Something plot-related should happen to your character in every scene that you can begin, complicate, and then end temporarily until the next scene.

- Beginnings (which I also like to call “launches”) should throw a lasso around the reader’s waist and yank her right into the scene. Skip explanations. If you can teach yourself NOT TO EXPLAIN to your reader—not to drop into backstory and justifications—you will already have a huge foot forward in writing scenes. Open scenes “in media res”—right in the middle of actions and situations.

- Middles are where conflict and drama ought to keep on happening. You don’t want to throw that lasso only to drag your reader into a puddle of stagnant water. The middle of a scene is where it only gets more complicated, interesting or tense.

- Endings of scenes stick in the reader’s mind, and also compel further reading. You never want your reader to feel as though they can stop reading! An ending is, therefore, merely a pause. But it might be a pause in which a character is hanging off a cliff edge, waiting for rescue. You are pausing, but not “comfortably.”

So now you are armed with the knowledge of a scene’s purpose (stylized, sexier simulacrum of real life that creates a sense of real time passing). You know its ingredients (Characters, action, setting, conflict/drama, plot—something “new” revealed to the reader that relates to the original situation). You have an idea on how to structure them (lasso of a beginning, complicated middle, cliffhanger endings). What are you waiting for? Make a scene.

Jordan E. Rosenfeld is author of Make a Scene: Crafting a Powerful Story One Scene at a Time, and, with Rebecca Lawton, Write Free: Attracting the Creative Life. She’s author of several suspense novels, Night Oracle (as J.P. Rose) and Forged in Grace, and at work on two forthcoming Writer’s Digest books: A Writer’s Guide to Persistence, and, with Martha Alderson, Deep Scenes. Visit Jordan at her website here.

Jordan E. Rosenfeld is author of Make a Scene: Crafting a Powerful Story One Scene at a Time, and, with Rebecca Lawton, Write Free: Attracting the Creative Life. She’s author of several suspense novels, Night Oracle (as J.P. Rose) and Forged in Grace, and at work on two forthcoming Writer’s Digest books: A Writer’s Guide to Persistence, and, with Martha Alderson, Deep Scenes. Visit Jordan at her website here.

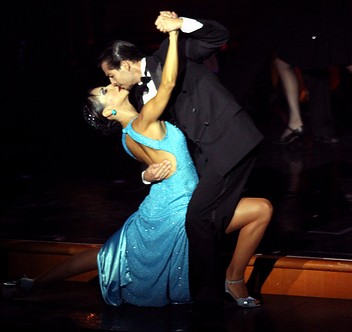

Featured Photo Credit: Prayitno/more than 2.5 millions views: thank you! via Compfight cc

Wonderful post on crafting a scene. The post itself even follows the way a scene should be written. Thank you for the info!

Thank you, Christine. I appreciate your feedback.

Your post arrives with perfect timing. I have started a new book, and this time around, I am really focused on crafting compelling scenes. Your advice that actions should be either character-significant or plot-significant is especially helpful. Thank you.

Best of luck to you in your new book writing journey, Michael.

This is a fantastic post! So well crafted, concise yet detailed, compelling and informative, not unlike a high quality scene 🙂

I especially appreciate the idea of starting a scene in media res, because while this seems so obvious upon reading, I don’t always do this – but I will now. Also, I am so grateful to your explanation that writing should be sexier than real life – how opening doors, walking across rooms, and getting in and out of chairs should be skipped. I often struggle to explain the mundane, thinking I have to, when of course I don’t!

Thank you for such an illuminating post. Now I just need to order your book 🙂

-Dana

Dana,

The idea of fiction being more dramatized/stylized than real life was something of an a-ha for me, too, years ago. It just makes it easier to get rid of the dull bits.

Thanks for a great post, Jordan! I appreciate you sharing your thoughts on scene construction and helping writers write better~!

This is a wonderful post. I always write my fiction with scenes in mind, and this just put it all in perspective. I actually feel very uncomfortable whenever I write to explain anything – and stop doing so pretty quickly or take it out. I do like writing descriptions, but try to make them relevant or a part of the action or a character’s perception in a scene. I love this: ‘Fiction is a stylized reality.’ I believe, even as a writer of Historical Fiction, that imagination is as important as actualities. Thank you!